BIOGRAPHY

Becoming Curator

In mid-1982 I returned to New Mexico with dreams of becoming a curator and, based on my experiences and acquaintances I made the previous year, determined Santa Fe was where I needed to be. It turns out that many creatives had made a similar calculation and converged in Santa Fe in the early 80s. As Stuart Ashman notes, it was a period when “it was still a collegial kind of relationship between everybody. And whenever there was an opening everybody was there.” (Ashman, 2017) It was a dynamic environment that quickly offered me opportunities to begin to chart a direction in the emerging new art scene. One such opportunity occurred when I was hired to install the Festival of the Arts exhibitions at the Sweeney Convention Center by Jon Hunner, who, as previously noted, had worked briefly for me at Contemporary Installations and had recently founded his own company: Art Handlers. The other installer on this job was artist Stuart Ashman, who would become a great friend and colleague and eventually succeeded me as Director of the Governor’s Gallery and subsequently serve as Director of the NM Museum of Art, Secretary of Cultural Affairs, Director of the Museum of Latin American Art (Long Beach, CA), and currently as the Director of Center for Contemporary Arts. Art Handlers would go on to become one of the premier art services businesses in the Southwest and, after selling the business, Jon Hunner would go on to become professor of History at NMSU, where he serves today.

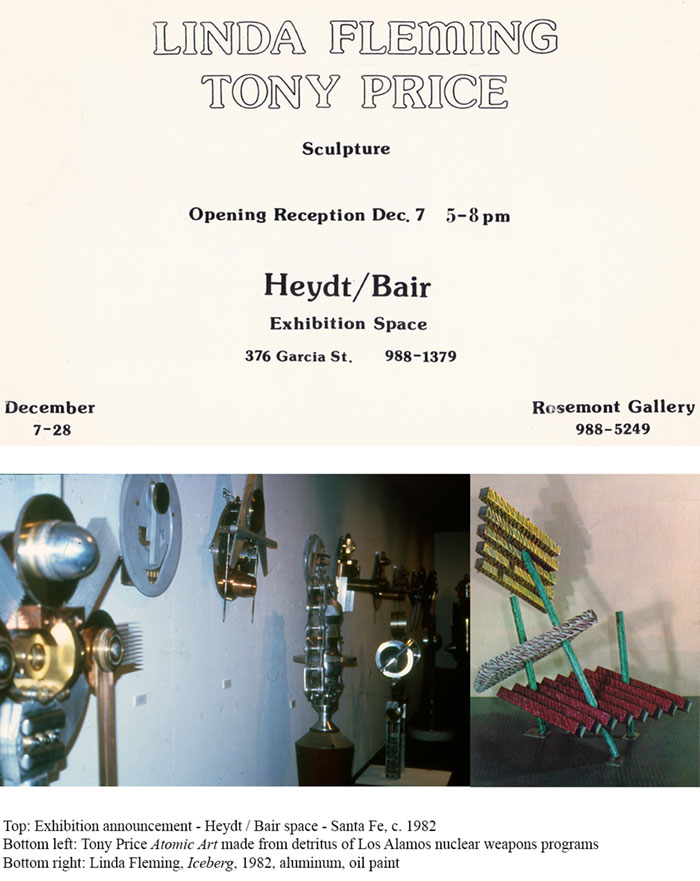

Around this same time I met artists Linda Fleming and Tony Price along with patrons and supporters Linda and Rosé Cohen, and Monte Ranes (of Rosemont Gallery). Together we hatched a plan to present a major exhibition of their sculpture, and, via my acquaintance with the owners, I was able to secure use of the space formerly occupied by the Heydt / Bair Gallery.

Price was known in the region for his work with the detritus from the nuclear weapons programs at Los Alamos, and his pieces struck a deep chord within me. The satirical dark humor embedded in his pieces provided a kind of metaphysical release of the negative energy associated with the cloud of New Mexico’s nuclear weapons history I had grown up with. Fleming’s work revolved around manifesting – in sculptural forms –the concepts of quantum physics. This show introduced a new body of her work in which she moved from years of working with hand-colored wood to forms of aluminum and steel. |

|

These artist’s works contrasted each other superbly in the ultra-contemporary setting, and as I spent time absorbing the essence of their efforts I can remember experiencing a kind of revelation about the true transformative power of art – an understanding that provided a foundation of my aesthetic awareness going forward, in much the same way as my experience with the Light and Space artists I described previously. This exhibition, essentially my first foray as a curator, was well received by the Santa Fe art crowd and represented a pivotal moment in my life and career. I would go on to have a decades long involvement with Tony Price and his work, and my friendship with Fleming would lead me to relocate to New York in 1983.

When I arrived in NYC the first order of business was to seek employment and I secured a position as a gallery assistant with Dyansen Gallery – one of the publicly-traded commercial gallery operations that were springing up during this period. A 1989 article in Schiff’s Insurance Observer referred to this somewhat shady business model as using “mass merchandising to sell ‘signed limited edition’ prints and sculptures, usually produced in lots of 300-500. [artwork] described as ‘fine art’ – a term that many critics would call a misnomer.” (Schiff, 1989)

The gallery was heavily involved in marketing multiples by the artist Erte and had hosted a 90th birthday retrospective the previous year. My job was to perform installations and other tasks for the owner and his gallery director son, and during my time there I was exposed to a different side of the art world, one in which galleries licensed the right to make “limited edition” reproductions that were “signed” using a mechanical apparatus that held a pen and placed the artist’s “signature” on blank paper that was later printed on – a far cry from the artistic and archival integrity of the original print world of Gemini and Tamarind. It was here that I learned invaluable lessons about the correct terminology in the print world, specifically the accurate definition of an original print – one that is produced manually by the artist in conjunction with a master printer from some type of plate that is subsequently destroyed or defaced to prevent further reproductions from being made. The art world is plumbed by this type of specific lexicon, and I have become increasingly aware that mastery of this idiolect is essential to working in the field.

One side perquisite worth noting from my time at Dyansen happened when I had the occasion to deliver some inventory to Miami at the same time Christo’s Surrounded Islands installation was in place. The image of the pink fabric floating on the blue water with the green island foliage rising in the middle was breathtaking, and seeing it in person was another transformational moment in my aesthetic awareness. In addition, witnessing the communitywide and nationwide reach of a major public art project such as this informed my understanding of the potentiality of art to influence society and define the culture.

During this same year I had the opportunity to meet sculptor Mark DiSuvero in his Long Island City studio and to visit the site that would become known as the Socrates Sculpture Park. I also traveled to Florida and assisted Linda Fleming and other sculpture collective ConStruct members with an installation at ConStruct South Sculpture Park at Greenwich Center in North Miami, and was able to visit the collection of uber collector and patron, Martin Margulies, on Grove Isle. These experiences helped to solidify my knowledge and love of outdoor sculpture which would manifest in multiple ways in subsequent years.

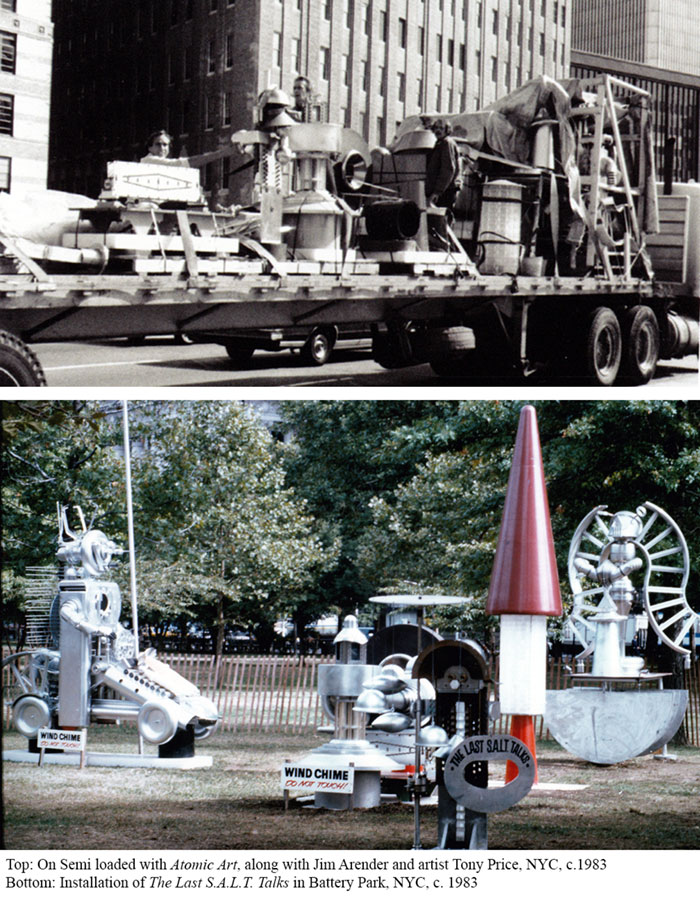

Meanwhile, back in Santa Fe, artist Tony Price and others were organizing an exhibition of his Atomic Art and in the fall of 1983 a semi-trailer loaded with several tons of his work arrived in Manhattan. Arrangements had been made to borrow a loft on the corner of Spring and Greene Streets in SoHo that had been made available by noted arts patron Ann Maytag, and I would serve as Director of the Atomic Art Gallery for the duration of the show. As I noted in my 2004 catalog essay, the exhibition was attended by several notables in the art and entertainment world and I consummated sales with several of these art patrons including fashion icon Diane Von Furstenberg and actors Anthony Quinn, John Phillip Law and Michael Green.

We had also obtained permission from the City of New York for a concurrent installation of Price’s work, The Last S.A.L.T. Talks, and a set of wind chimes made from atomic bomb casings in Battery Park. The display garnered an article in the NY Times which included the following reference by a City official: “Henry J. Stern, the Parks Commissioner, was on hand for the opening of Mr. Price's exhibit. ‘It's good, art as a statement,’ he said of the work, which stands near large stone tablets bearing names of war dead. ‘And it's very appropriate next to the war memorial. In the next war there won't be any memorial.’” (Anderson, 1983) Click here to view article >> |

|

In addition, the newly formed news organization CNN produced a brief segment on this work in Battery Park. Central to the significant media coverage we received was our work with a well-connected NYC public relations firm Fenton Communications (brought to us by Price’s father-in-law the renowned NYC entertainment lawyer David Lubell) and the marketing and PR skillsets I cultivated at that time have informed my work in the field ever since.

Complementing the gallery exhibition and Battery Park public display was a screening of the film Atomic Artist by Glen Silber and Claudia Vianello, which our team presented at a benefit for the Film Fund at Greene Street Cafe (owned by Tony Goldman, pioneer of the revitalization of SoHo in the 70s and 80s). This tie-in with a well-respected non-profit organization allowed us to engage the supporters of the Film Fund and patrons of the popular SoHo eatery and jazz club in a win-win situation that exposed them to the work of Price and this poignant documentary film, while raising money for an important charity. This kind of collaborative model is one I would re-purpose numerous times over the course of my career and which exemplifies the power of visual art to connect across various interests, disciplines, and social strata – a powerful dynamic that has been at play for centuries as eloquently summed up in the following quote credited to Leopold II, King of the Belgians from a letter to Queen Victoria in 1845: “Beware of Artists! They mix with all classes of society and are therefore the most dangerous.” (RE:ARTIST, 2016)

The accomplishments noted above would seem to indicate that we had successfully claimed a place in the big-city art scene but there were a few more unforeseen challenges before the end of this undertaking. During the weeks following the installation of the works in Battery Park the sculptures sustained significant vandalism and theft. The decision was made to find another venue where the pieces could be removed to and Tony Goldman offered the use of a vacant loft space a few doors down from Greene Street Café. A crew was assembled and the sculpture components were unceremoniously loaded on a truck and moved to SoHo where Price, myself, and a few volunteers began the process of re-assembling The Last S.A.L.T. Talks in the interior setting.

After several weeks the installation was ready to be viewed again but, just as we were about to open the doors to the public, the NYC Loft Board showed up to inform us that the space we were in was prohibited from being occupied as a result of numerous previous violations by Goldman. As we grappled with the question of what to do next in the face of an impending deadline to vacate the premises, we were introduced to Soviet ex-pat art dealer Eduard Nakhamkin who had been converting a 12-story building at the corner of Broadway and Houston into gallery spaces.

Although, according to a 1981 NY times article his focus was “foreign galleries, which, Mr. Nakhamkin says, find it difficult and expensive to take temporary rental space when they exhibit art at expositions here,” (Oser, 1981) Nakhamkin took an interest in the anti-nuclear statement of Price’s work and offered a 10th floor space at a reduced rent. We set up an impactful installation and proceeded to publicize the exhibition. As the much-presaged new year of 1984 came we found ourselves tired and more than a bit disillusioned – and after exhausting efforts to identify private collectors and various unsuccessful attempts to place works in public setting such as Hofstra University and others, it became clear that what had been missing all along from the entire endeavor was a thoughtful exit plan.

As the decision to pack it all in and send the work back to NM became inevitable, there was one unanticipated side distraction from this period – artist Keith Haring had rented the basement space in the Nakhamkin building for the purpose of holding a month-long party to coincide with his “Into ‘84” exhibition at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery around the corner on Mercer St. It was certainly a happening scene, and although our efforts with Price’s work were not producing the hoped-for results, the proximity to Haring’s extravaganza gave us the sense that we were part of something bigger than ourselves.

Indeed, the entire NYC project was a defining moment in my career as a gallerist, and I was buoyed by the many lessons learned, the skillsets I had obtained, and the people I had interacted with. The work I had done provided important resumé material that would prove to be instrumental in securing future positions – most specifically when I was in the running for Director of the Governor’s Gallery.

Returning to Santa Fe in 1984 I was able to leverage my NYC experience as gallery director and project manager to re-engage within the Santa Fe arts community. Over the following two years I provided various services to galleries and individuals, coordinated exhibitions of Jamie Ross at the Village Fool, Antonio Alvarez at the Telluride Film Festival, and collaborated with Linda Cohen under the moniker RutCo to curate exhibitions of neon art at nightclubs Club West and The Launch Site.

It was also during this period that I would first meet Chuck Daily and assist him with installation of exhibitions at the facilities housing the Institute of American Indian Arts at the Santa Fe Indian School – the beginning of a long-term relationship with the Institute that has included my exhibition of artwork by numerous IAIA students, hosting and assistance with various fundraising activities and events, and continues today as a patron and student myself.

In 1985 I was invited to serve as one of the curators, along with Stuart Ashman and Nancy Sutor, for the second Space X exhibition at the Armory for the Arts. The show featured 111 works by fifty artists, and was, in the words of writer Nicole Plett, “a more considered project than its predecessor, but by no means less boisterous.” (Plett, 1985) She goes on to state that “Space X 1985 is a Salon des Refuses only in the sense that the majority of the work on exhibit is not by the state’s mainstream, gallery-represented artists. Many have been seen locally, however, over a period of years, in a variety of invitational and juried group shows. Some are clear newcomers” and quotes project director Stuart Ashman who observed that “The show asserts the fact that we are an art community. This is the scene.” She concludes by stating that: “Space X 1985 is a show that should be seen to be believed.” (ibid- Click here to view article >>)

Continued on page 3 >>

|

Click to view Abstract, Acknowledgements, Dedication, and Bibliography

|