BIOGRAPHY

Pushing the Exhibit Boundaries

In addition to those noted previously, there are several other exhibitions and projects from this period which stand out for me as the most memorable, popular, satisfying, inspiring, innovative, or otherwise noteworthy. Separate exhibitions of photographs of New Mexico from the 1930s and 40s by John S. Candelario and Ernest Knee were rare opportunities to see work by these photographers. Shows we co-hosted with organizations such as Very Special Arts, the New Mexico Veterans Service Commission, the New Mexico Art Education Association, and the New Mexico Watercolor Society presented the public with the chance to see works not readily accessible in traditional gallery and museum settings and offered participants the recognition of being shown in a high-profile setting and, as Stuart Ashman notes, “the prestige and recognition that comes from having the Governor and First Lady come to their opening.” (Ashman, 2017)

Thematic group shows such as New Mexico Flora, New Mexico Landscapes, New Mexico Petroglyphs, New Mexico Watercolor Society, The West in Paint & Bronze, and Portraits of New Mexicans were exhibitions that provided a more in-depth examination of specific subjects that were in some way unique to our state. In addition to their appeal to Gallery visitors, group shows such as these gave me the opportunity as curator to recognize and give exhibition resumé material to numerous artists who, due to time and space limitations, may not have ever had solo shows at the Governor’s Gallery.

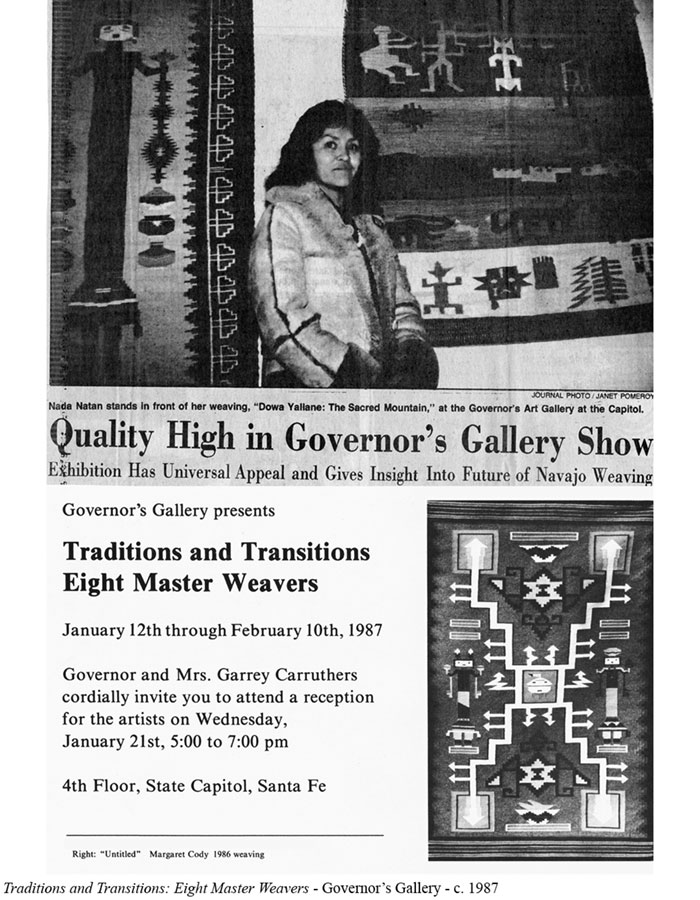

Solo exhibitions – some for under-recognized artists such as Una Hanbury and Ila McAfee, and others for more prominent artists like Dan Namingha and R.C. Gorman – offered visitors a more comprehensive overview of their respective careers to date. Still other exhibitions such as Traditions and Transitions: Eight Master Weavers, and shows for John Catterall, David Winston, Ken Barrick, and others fulfilled an inclusionary mandate by bringing to Santa Fe artists from the far reaches of the state. (Click to view exhibitions >>) |

|

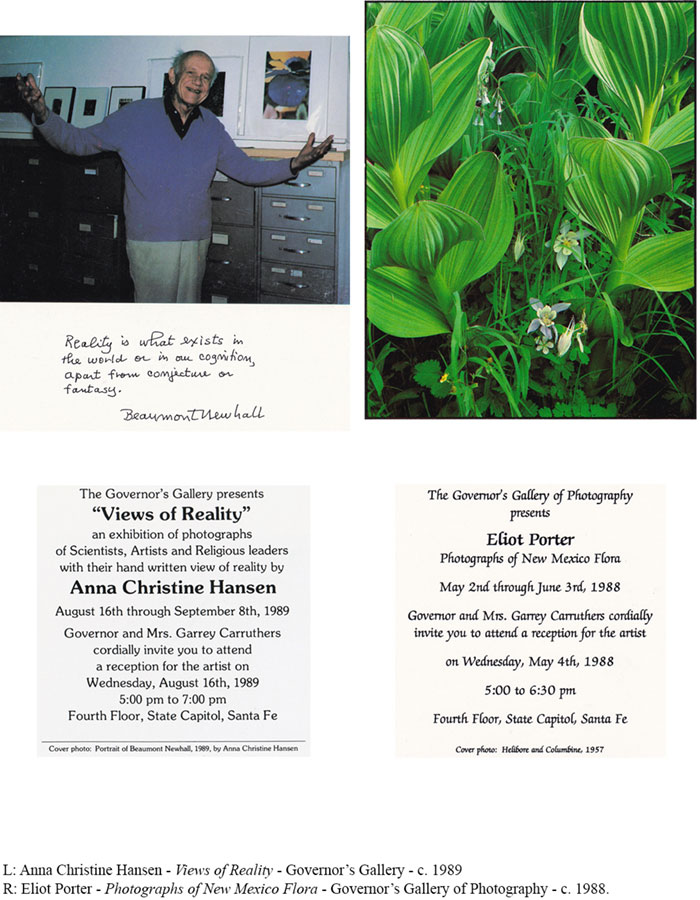

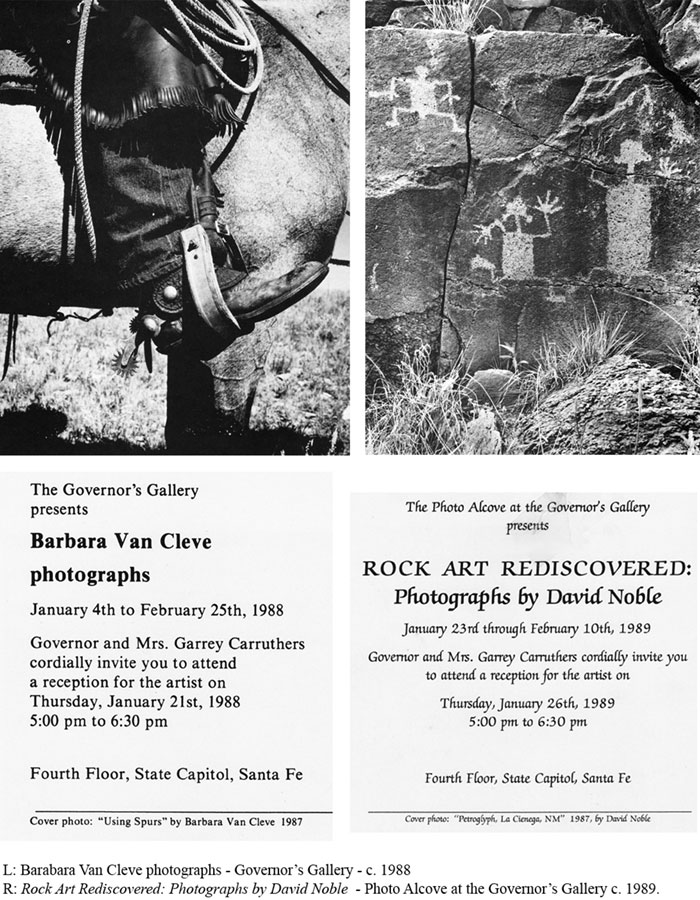

Exhibitions for photographers, Barbara Van Cleve, Walter Chappell, David Noble, Barbara Zusman, Ana Hansen, Paige Pinnell, Eliot Porter, Barbara Simpson, and others highlighted the creativity and diversity within the medium and spurred the decision to dedicate an additional space within the Governor’s Office confines (dubbed the “Governor’s Gallery Photography Alcove”) to stand-alone displays of photography.

(Click here to view exhibitions >>) |

|

|

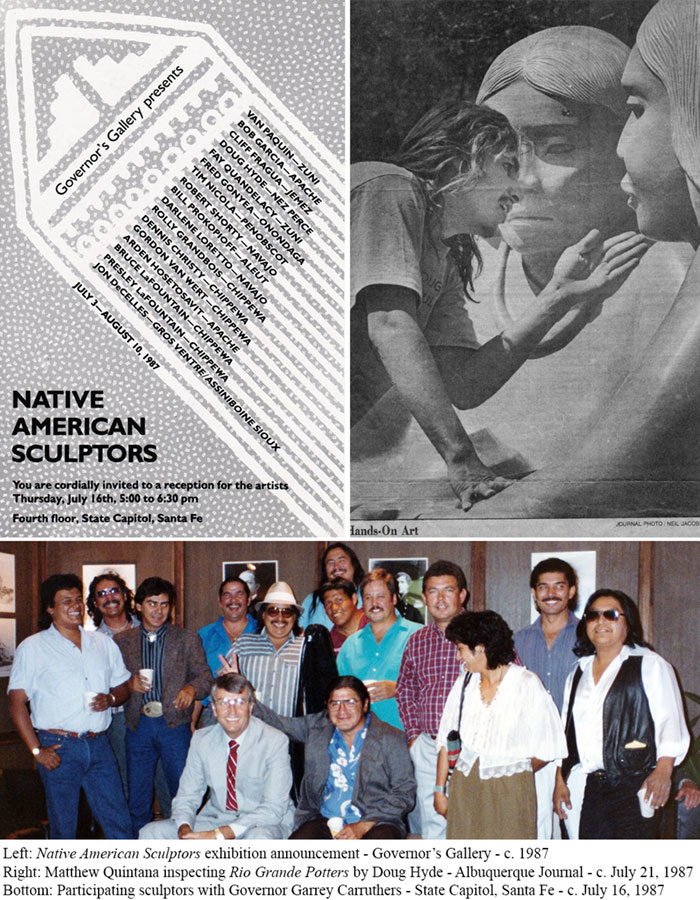

The two largest Native American group shows I organized were the result of relationships I had established in the Native artist community and were examples of the diversity I was attempting to bring to the program. In retrospect, I now realize just how significant they were in terms of the development of my own understanding of the aesthetics and visual language of Native art and the social and institutional dynamics that were at play during the mid 80s. It was a time, as Lloyd Kiva New noted, when Native art was finding “a bona fide place within the hierarchy of the universal art world and propelled it into the stream of American commerce.” (American Indian Art, 1984)

Indeed, several of the artists included in these shows would go on to be highly successful leaders in the field. There was also significant activism on the part of Native artists (such as David Bradley) locally around the issues of the exclusion of artists of color by institutions, and “pseudo-Indian” artists passing themselves off as Native. Native scholar Suzan Harjo said of Bradley; “David also has a social conscience and is not one to stand by and watch injustice take place. He worked with other young artists in New Mexico to form the Native American Artists Association, which promoted Native artists and tried to curtail the proliferation of pseudo-Indian artists, who not only passed off their work as ‘made by Native people’ and displaced real Native artists, but who took over as authentic voices of Native Peoples.” (Bradley, 2013)

Bradley’s efforts placed New Mexico at the forefront of the emerging debate about multi-culturalism in the museum and art world as they paralleled the national social activism of groups such as the Guerilla Girls. As a young curator my awareness and understanding of these topics was greatly enhanced by their work, and the activist foundations that were laid at that time continue to inform my practice to this day. |

|

Complementing the range of exhibitions noted above were certain endeavors that I feel were particularly good ideas that seemed to manifest from moments of clarity or flashes of inspiration. The first came about in response to the impending relocation of the governor’s offices due to an estimated two-year closure of the Capitol building for the removal of asbestos and overall facilities upgrades. Faced with the very real possibility that the Governor’s Gallery program would simply be discontinued, I conceived of a plan for travelling exhibitions that I would organize and transport to various facilities in other parts of the state during the interim.

Part of the advantage and appeal of the Governor’s Gallery “On the Road” plan was that it would achieve our goal of serving a statewide constituency by offering compelling and diverse exhibitions free of charge to institutional venues – many of whom had limited exhibition budgets – while generating positive publicity and attention for the artists and organizations involved, as well as the Governor and First Lady (and securing my job until the Capitol re-opened).

Among the traveling exhibitions of note was Printmaking in New Mexico: A Native American Perspective at the Stables Art Center in Taos – which Taos News writer Deborah Ensor noted was a show that made “a statement about Native Americans facing a contemporary world and contemporary issues. It makes that statement boldly, colorfully, and sometimes whimsically.” (Ensor, 1990 - click here to view article >>) There would be continued convergence of these themes of Native identity and modernity in my future work as a curator and again recently in my academic studies.

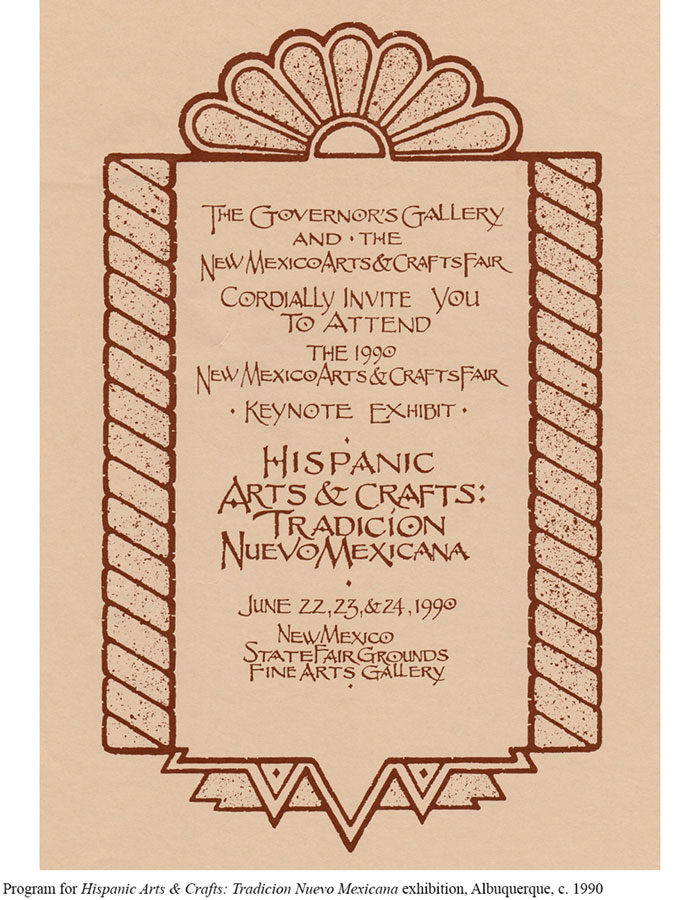

Perhaps the most high-profile exhibition from the Governors Gallery “On the Road” schedule was the keynote exhibit I co-curated with Victoria Plata from the Hispanic Culture Foundation for the 1990 New Mexico Arts & Crafts Fair (NMACF) at the NM State Fairgrounds Fine Arts Gallery entitled Hispanic Arts & Crafts: Tradicíon Nuevo Mexicana. As noted in our curatorial essay, the fifty-one artists selected for this exhibition represented a cross-section of “some of the finest traditional and contemporary Hispanic artists working today” and included many “art forms and imagery [that] are indigenous to New Mexico, often passed down through generations” as well new expressions that “broaden the definition of what Hispanic art is.” (Rutherford & Plata - click here to view essay >>)

Assembling a show on this scale to include a diverse group of works, mixing both traditional and contemporary art forms, was somewhat groundbreaking in that the common methodology practiced heretofore in exhibitions of Hispanic artists was to not show both styles together. Our effort was also noteworthy in that an exhibit of such importance had never been presented as a keynote for the NMACF – even though the Fair had traditionally been one of the most visited art events on the state for many years. |

|

Images of that glorious installation are still etched upon my mind, as is my appreciation for the dedication and personal soul of the artists I met while visiting homes and studios in the course of our selection process. My sentiments are echoed in the words of author E.A Mares (reproduced in the exhibition program): “For the Hispanic artist, space and time and all they contain are sacred. This quality of sacredness will continue to permeate the creations of New Mexico’s Hispanic artists in the future. We need to conserve our distinctive artistic relics for the future even as that future unfolds, even as new art forms arise for which no words exist.” (Mares, 1999 - click here to view essay >>)

Continued on page 5 >> |

Click here to view Abstract, Acknowledgements, Dedication, and Bibliography

|