BIOGRAPHY

The artistic endeavor that stands out for me as one of the most innovative and clever is a plan I came up with to create a statewide Month of Sculpture and a corresponding city-wide exhibition dubbed the Mile of Sculpture. The concept grew out of conversations I had with the Museum of Fine Arts curator, Sandy Ballatore, about possible collaborations that would leverage and enhance her upcoming exhibition entitled Singular Visions: Contemporary Sculpture in New Mexico – a major show featuring the work of 26 sculptors including such luminaries as Bruce Nauman, Elliot Norquist, Terry Allen, James Marshall, Bob Haozous, Luis Jimenez, Erika Wanenmacher, and others.

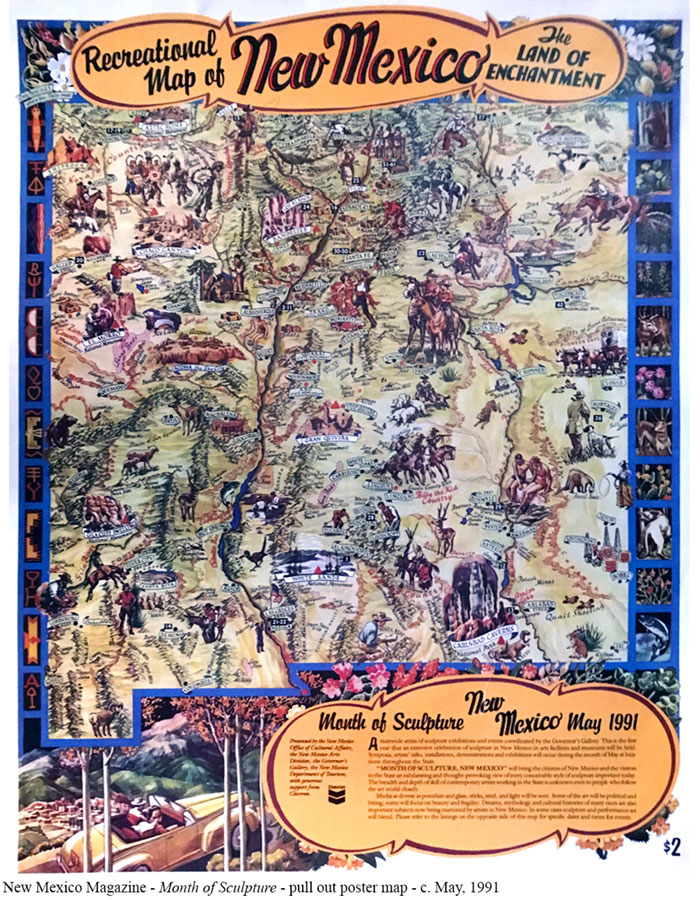

The ideas for how the Governor’s Gallery could participate came to me in what I can only describe as flashes of inspiration – serendipitous occurrences, seized through being open and focused in the moment, that ended up having large impacts. The first came when I was visiting a friend’s vintage store in Albuquerque and spied an illustrated map of New Mexico produced by the State Tourism Department in the 1940s. As I looked at the period illustrations of cowboys, sportsman, wildlife, historic sites, and natural wonders, it occurred to me that this map could be re-purposed to promote sculpture exhibitions and installations.

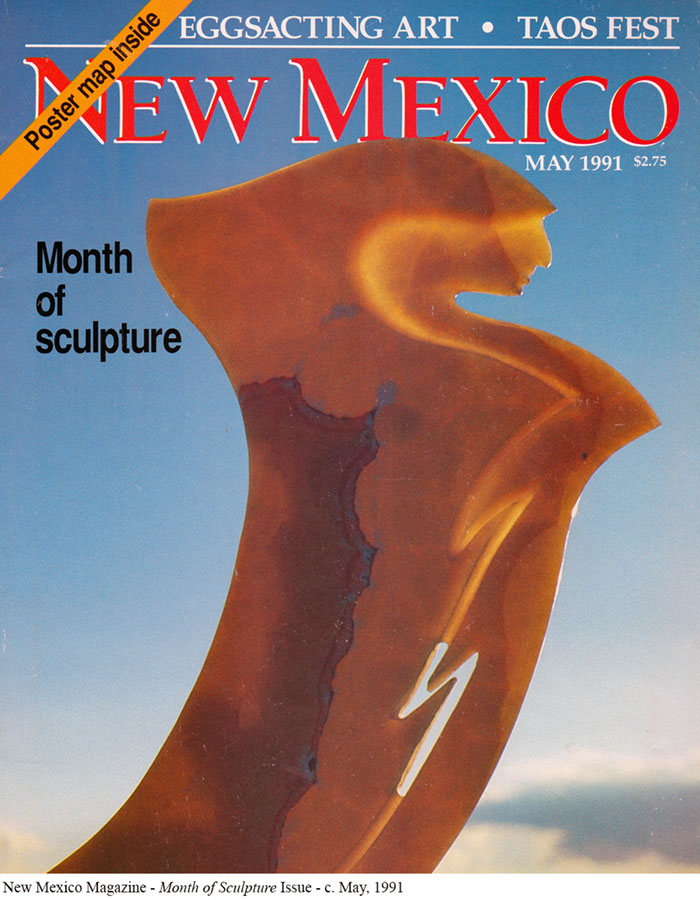

I ran with the idea and set about contacting public and private venues around the state inviting them to participate in Month of Sculpture. In the end, 62 venues in 20 cities were listed on the reprint of the map – many of whom developed exhibits and programming specifically in response to my call. New Mexico Magazine ran a cover story and included the re-purposed vintage poster/map as a tear out (click here to view article >>).

|

|

|

Writer Mary Carroll Nelson wrote of the project’s genesis:

Rutherford visualized Ballatore’s contemporary show as the lead-in for related exhibitions across the state, focused on sculpture, widely varied in style and scale. His expansive attitude bridges a largely unconscious but formidable Mason-Dixon Line that in the past has divided New Mexico’s art life into north and south; likewise, he has expanded the cultural corridor bounded by the Rio Grande Valley from Taos to Las Cruces into border-to-border inclusiveness. (Nelson, 1991 - click here to view article >>)

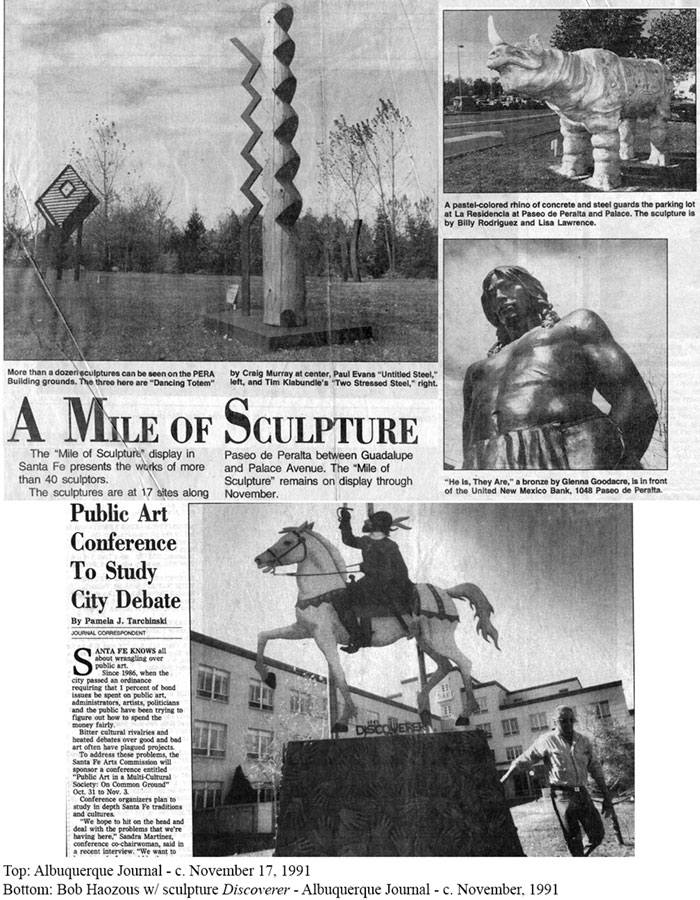

The idea for Mile of Sculpture came to me one day as I was driving from the NM Arts Division to the Governor’s Office along Paseo de Peralta – a one-mile avenue that forms a horseshoe around downtown Santa Fe. As I reflected on the ongoing displays of outdoor sculpture on the Capitol grounds, I noticed the many open spaces along my route and imagined them sporting installations of sculpture. I conceived of a plan to identify a list of artists who would be willing to loan works and matched them with a list of businesses and public properties willing to offer space for their artworks.

The plan proved to be wildly popular and generated numerous newspaper articles and other media coverage. Writer Gussie Fauntleroy referenced the public response in an article in Pasatiempo:

From the public, heads have been turning, cars slowing slightly, walkers stopping, staring, touching, talking to each other about the creations…“It’s a lot of fun putting big art outside in public places” Rutherford says. “The audience increases exponentially, and it seems to affect the public in mostly positive ways. It’s something that will cause people to realize Santa Fe is a vibrant art community.” (Fauntleroy, 1991 - click here to view article >>)

|

|

These two projects combined fulfilled important goals by engaging the public and the media around public art and elevating the state’s stature as an art center. In addition to the significant statewide participation and extensive press coverage, the projects inspired a dialogue at related events such as a sculpture symposium sponsored by the Stables Art Center in Taos and a public art conference entitled "Public Art in a Multi-Cultural Society: On Common Ground” sponsored by the Santa Fe Arts Commission and partially funded by the NEA. These conversations were made more salient by a controversy surrounding a work by artist Bob Wade that I had included in a display at the P.E.R.A. building across from the Capitol. The work, entitled Fetish por Los Tres Gentes, was a fabrication perched atop a 40-foot pole that was built around the side panel of a 1950s Chevy with flames painted on the side, a ski rack with skis, a cell phone antenna on the top, and an image of a buffalo head on the front. Wade described the content as tongue-in-cheek, satirical references to common cultural stereotypes – with the buffalo referencing Native American culture, the skis and cell phone antenna referencing Anglo culture, and the car body referencing the Hispanic car culture of Northern New Mexico.

It quickly became apparent that the artist had struck a racially sensitive chord within the community when, after several newspaper articles, letters-to-the-editor, and days of relentless condemnation by former Mayor George Gonzales (father of current Mayor Javier Gonzales) on his radio station, the work was chain-sawed down by vandals in the middle of the night. A newspaper story by Peter Eichstaedt commented that “critics said the car body was not a fair representation of Hispanic culture” and quoted the artist who stated “It triggered something. It was something with the iconography that has upset them. It does have some power to (critics).” In the article, I also give my assessment: “‘My job is for the work to be seen’ Rutherford said. ‘The sad thing for me is we were just about to get into a dialogue about this. If I had thought this piece was derogatory to Hispanics I would not have put it up. The idea was to create some lightheartedness, not at the expense of any one group.’” (Eichstaedt, 1991) |

The epilogue to this story came a few days later when Wade came up with a classic response to the controversy by creating a work to be installed in place of the vandalized piece. A subsequent story by Eichstaedt featured a photo of Wade, assisted by artists Paul Sarkisian and Larry Ogan, installing a wooden cross complete with a photo of the sculpture surrounded by plastic flowers and lined with tiny shimmering metal disks – emulating the roadside markers or descansos common in the Southwest that are placed at the site of a violent, unexpected death, in memoriam. I am quoted in this article saying “This is Bob Wade’s gesture of peace for the community. Hopefully it will stand for reconciliation.” (Eichstaedt, 1991)

Continued on page 7 >> |

Click here to view Abstract, Acknowledgements, Dedication, and Bibliography

|